James Richard O’Connor

(Apr 20, 1930 – Nov 12, 2017)

CPE is now offering the opportunity for those who want to contribute financial support towards a conference scheduled in Jim’s honor to be held June 29th – July 1st, 2018 in Santa Cruz, CA. More details to follow. Please use the Buy Now button at the bottom of this page to make your tax exempt contribution. Write “conference” in the Project-specific donation box. Thank you!

Michael Goldman

Jim was an intensely driven, passionate, and creative human, friend, scholar-activist, and intellectual who lived each day based on deeply held principles of social justice and revolution. His contributions to the understanding of the workings of capitalism and the state have been monumental. His work has been translated and debated in dozens of languages all over the world, and remain essential for social movement activists and teachers fighting against the catastrophe called capitalism. Before retiring as professor of Sociology at UCSC due to severe chronic back pain, he started an international journal, published a series of books, and kicked off an international discussion on capitalism and the environment in ways that still thrive in universities and public spaces everywhere. His ideas live on and remain sustenance for young students everywhere navigating their way into the world of scholar-activism.

Besides the idea of revolution, his greatest love was his companion for many decades, the lovely Barbara Laurence, who kept Jim grounded in love, in the world, and with friends and music and good cooking. Barbara gave her all to Jim, giving angelic care, especially in his last years, when Jim’s illness overtook him. Jim will be missed sorely by family, friends, and comrades the world over. (Michael Goldman)

Giovanna Ricoveri

James O’Connor’s intellectual and political contribution to social sciences has been important, although not enough recognized. His formulation of the second contradiction of capitalism – that between capital and nature– has been crucial to understand the crisis of mature capitalism in the last decades of the XX century and that of the European social democracy to deal with it. For me, he has been a long time loyal friend and “a master”.(Giovanna Ricoveri)

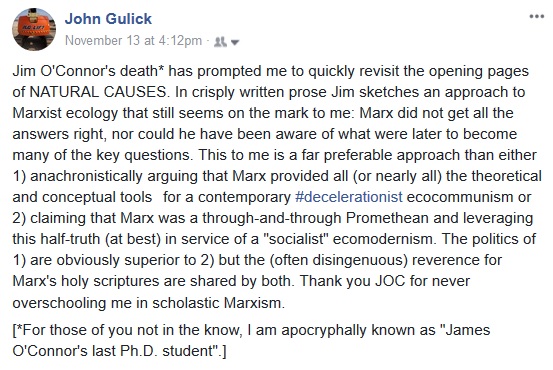

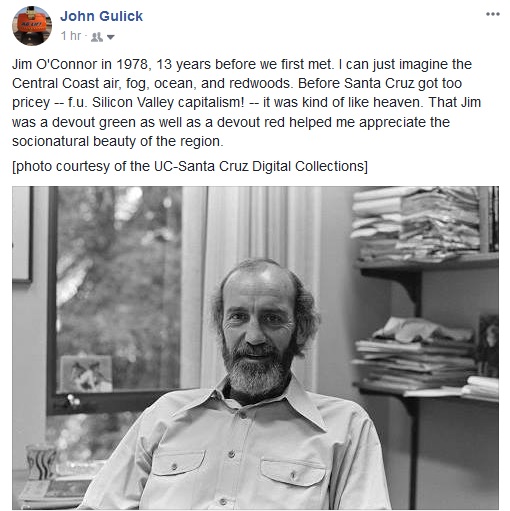

John Gulick

Stuart Rosewarne

Vale James O’Connor

The passing of James O’Connor marks a significant moment in the history of Marxist scholarship and politics. Born in 1930 and growing up in Boston, a short stint in the merchant marine introduced him to a world beyond the oppressive cultural and political environment of Cold War America. This aroused his interest in a more critical engagement in understanding the world beyond capitalist America. He completed studies in economics and sociology before working on a doctoral thesis exploring the forces that had resulted in the Cuban revolution, a study, which was subsequently published under the title of The Origin of Socialism in Cuba in 1970

This set him on the path as a warrior, along with others such as Joel Kovel, as a radical in the face of the cultural wars that were unfolding with the civil rights movement, feminism and student movements. He joined an emerging group of young intellectuals interested in drawing on the writings of Marx and other radicals intent on critiquing capitalist hegemony. He was intent on reinvigorating debate within Marxism and investigating established interpretations of this tradition to forge an invigorated Marxist analysis of capitalism, first publishing a series of reflections that contributed to exposing the nature of American imperialism and the unfolding contradictions with global capitalism.

After some teaching positions on the east coast, Jim took up academic positions in San Francisco where he joined a cohort of other radical thinkers in the early 1970s, and where he began to really make his mark on radical thinking and politics and particularly Marxist discourse. His particular focus concentrated on interrogating the role of the state in contemporary capitalism, and he drew together similar thinking colleagues to debate and develop critique. He led the way in setting up the journal Kapitalistate in 1973. The journal brought together comrades from the San Francisco Bay Area and from across North America and the world, including Italy, Germany and the U.K. His own thinking was developed in The Fiscal Crisis of the State, a pathbreaking analysis of the fundamental contradictions inherent in the role of the state’s inability to reconcile all of the claims for resources being made on the state. The Fiscal Crisis firmly established his standing as one of the foremost Marxist critics of the era.

The originality of The Fiscal Crisis lay in the innovative approach to drawing on Marxian categories to rethink how we should analyse the state. This capacity to revisit Marx’s concerns was also demonstrated in subsequent publications that concentrated on the multiple crises of capitalism, with the publication of Accumulation Crisis in 1986, followed by The Meaning of Crisis in 1987.

Settled in Santa Cruz at UCSC, and drawing on Barbara Laurence’s enthusiasm for protecting the red wood forests on the Californian coast, Jim turned his attention to the environmental destruction being wrought by the capitalist system. Indicative of his longstanding efforts to encourage others to join in and develop critiques of contemporary capitalism, he, Barbara and others, fostered a coterie of graduate students to contribute to this developing critique. He reconnected many of his old comrades to focus on the environmental question and established the journal Capitalism Nature Socialism as a global enterprise and the Center for Political Ecology.

Once again, Jim returned to exploring ways of creatively building on Marxian categories to reformulate how we might go about interrogating capitalism’s destructive force. Incorporating insights from Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation, Jim posited the notion of ‘the Second Contradiction’ of capitalism, the inherent tendency for the process of capital accumulation to undermine the natural (environmental) conditions of its existence. This concept contributed, if not spearheaded, a dramatic engagement of Marxists and other radicals in recasting their critical focus on the environment.

The formulation of ‘the Second Contradiction’ was posed in opposition to the shift in radical discourse that had been influenced by post-structuralist thought and which had jettisoned Marxist theory to privilege the place of social forces, other than class. Jim was determined to re-establish the import of the working class in the forging of a progressive politics, and this prompted some intense and often acrimonious debate, not always confined to the battle for intellectual primacy in understanding the force of social struggle. But the significance of the notion of ‘the Second Contradiction’ lies in the extent to which it has become a foundation, or reference point, for the extraordinary growth in radical analysis of the array of environmental problems across the global.

Jim will be remembered by friends and foes alike, as well as those who he encouraged to join the cause, as an iconic figure in our efforts over the last fifty or so years to rebuild the force radical discourse and to take control of our political future. Over the last decade or more, he was working on extending this project by developing a critique of the many contradictions embedded in the processes of globalisation and neoliberalism, a project that remained frustrated by ill-health. However, he leaves behind a remarkable legacy that will continue to frame and inform radical analyses of capitalism’s many contributions well into the future. (Stuart Rosewarne)

James O’Connor’s intellectual and political contribution to social sciences has been important, although not enough recognized. His formulation of the second contradiction of capitalism – that between capital and nature– has been crucial to understand the crisis of mature capitalism in the last decades of the XX century and that of the European social democracy to deal with it. For me, he has been a long time loyal friend and “a master”.(Giovanna Ricoveri)

So I’ve been in a planning grad program for 2+ months and it was not until today that I began assertively inserting an ecological Marxist perspective into classroom discussion. Before, as an older and — possibly, in some respects — wiser student, I did not want to aggressively crowd out other voices, or agitate my professors (especially those of a liberal-reformist mainstream bent). But now, JOC is gone and I’ve been reawakened to carry on his ideological and political legacy.

To read Louis Proyect’s reflection of Jim O’Connor on his blog, visit: https://louisproyect.org/2017/11/14/reflections-on-james-oconnor-1930-2017/

I realize now that many of our failures in the 60s stemmed from our more fundamental failure to follow the best among us. For me that was James O’Connor. He was understood by many to be the most imaginative and courageous leader, as well as Marxist economist, who really tried to “put Marx back into Marxism.” I felt that he was leading the way but only few were following. His leadership was always collective, and he was in search of gifted students who were interested in communism. He set standards for debate, for theory, for relating theory to practice (particularly in regard to the sixties strikes happening at the universities of UC Santa Cruz, San Francisco State, San Jose State, and Berkeley). He opened up the whole field of Marxist ecology with the understanding of why Red had to be simultaneously Green. In the process he founded two important journals together with his comrades. One was Kapitalistate, which took on the task of developing a theory of the state that was Marxist through and through. The other was Capitalism Nature Socialism, which tried to set the foundation for a Marxist ecology movement. And it was him more than any one else who tried to study the nature of corporations, and who talked about the corporate form of organization.

Now that he has passed away, it is my opinion that his death has left a gaping hole in what is left of the movements that came out of the sixties. Again and again, he sought a genuine Marxist solution to the problems that came up within the struggles; however, he was anything but orthodox when it came to his Marxism. He was able to leave plenty of room for imagination and courage in his vision of a socialist world and the revolutionary possibilities he left to us, especially in ecology. The contradiction between capital and nature, what he called the “second contradiction of capitalism” (the first being between capital and labor), was one of his greatest conceptual innovations and one that remains perhaps even more important than ever now that more and more people recognize that we face an impending ecological catastrophe. We have to learn to spot this contradiction wherever and whenever it appears. He was the biggest intellectual influence of my life. He was my mentor, always pushing me for more rigor and depth in my writings. Together with people like David Harvey and Fredric Jameson, he pioneered a reinvigorated Marxism for today. It was a pity that we didn’t follow his lead more, and I have no doubt that his work will be of vital importance for the future.

Jim was one of the few I looked up to. A man of high quality, focused and channeled intelligence and deep critical perspective; he taught me more than I could ever thank him in this lifetime; about economic systems, human nature, power and conflict (micro and macro); about etiquette and culture; art and music, good food and about the importance of struggle as well as the value of hard work and importance of making your passion your work. Most importantly he gave me a lot of love that flowed when I really look back, unconditionally. He came from a fairly hard background; he was sent away at 10 years old once his grandfather died; his father wasn’t there for him like he was for me. He had a long, fascinating and productive life; he joined the Merchant Marines as a teenager and sailed into Europe in 1947 and as he conveyed to me one time “saw the wreckage of world war;” he joined the US Air Force and became a Sergeant; he leveraged the GI Bill to go back to school and embarked on what became a notable academic career–influencing political & economic thinking and supporting political movements along the way. He met my mom who was one of his students and for that I’m grateful…He carried within his soul a deep resentment toward inequality and injustice (he used to say “throw the bosses out the window”) and was a powerful force (at least in my eyes) in contributing to the collective project to make our society a better, more humane and decent place. For that I am grateful for all eternity and I hope I see him again when I check out.

My respect and loyalty for Jim is grounded in his political activism during his days in Cuba helping to stabilize the revolutionary government; his leaving relatively safe New York for the dangers awaiting his bus caravan to the South during the Freedom Rides; and his part in organizing the Faculty Against the War during the horrible days of Viet Nam. Through the eyes and devotion of his many graduate students, and those who looked to him for leadership in the world of academia and publications, my pride grew from becoming the chosen one who gained his trust to a partnership of more than thirty years. I am one of a large group of people who were challenged by Jim to step up and accomplish more than we thought we could do. I am very proud that I helped Jim get many of his ideas down on paper. Those of you who were influenced by those ideas are collateral beneficiaries of my love story. That story is now over. I will miss Jim for the rest of my life.

We mourn the sudden loss of a visionary and highly influential thinker, James Richard O’Connor, founder of Capitalism Nature Socialism with Barbara Laurence, his life-long companion. O’Connor was a rigorous, indefatigable intellectual and a committed Polányian Marxist activist. His thoughts have reached and shaped the minds of thousands of people, including mine, and I trust thousands more will benefit from his insights. He wrote on a wide range of subjects of great political consequence and of continuing currency and urgency today. This includes explaining, in his early works, the relationship between capitalism and the state, as well as clarifying linkages between imperialism and economic processes. The Fiscal Crisis of the State is only one of the better known of his writings that emerged from this line of research. It remains a classical piece, and one that should be read even more widely and translated into more languages than it is. O’Connor also contributed to great theoretical strides for all of us in the journal through his latter endeavours on the ecological crisis, especially in the latter part of the 1980s. This, to me, is the germinal intellectual turning point that oversaw, with the establishment of this journal and the Center for Political Ecology, the confluence of left-leaning ecological thought with a diversity of leftist anti-capitalist approaches, including variants of Marxism and feminism. The creative and illuminating outcomes of this confluence and, to a large extent, interweaving of then (and still now) disparate currents are among the lasting legacies bequeathed to us through O’Connor’s efforts. The development of his Second Contradiction thesis is but one shining example of what came about through such confluence of approaches and it continues to be an inspiration (or source of debate) for many. O’Connor’s formidable intellect was complemented by political commitment. This was reflected in, among other actions, his involvement in local environmental struggles. Part of this kind of activity was consumed by writing pamphlets accessible to a wide readership, including for the Students for Democratic Society’s educational campaigns in the 1970s and for various environmental and social policy activist groups in the 1980s. His political commitment was also represented by his networking and organising with intellectuals across continents to bring to the attention of North American audiences news, perspectives, and analyses of social and environmental struggles in different parts of the world. He facilitated such international information flow by creating a network of journals from Catalunya/Spain, Italy, and France, based on reciprocity and free manuscript exchange. This is one major way in which this journal came to have an international breadth and reach, as well as benefit from the input of thinkers from many countries. James O’Connor struggled in an inimical intellectual world to keep Marxist perspectives alive while critically reconstructing them to overcome their historical inadequacies, especially with respect to ecology. In all this, he did not mince words, maintained a clear political line, yet kept this journal from falling under any particular tendency, including his own. Farewell, Comrade O’Connor, intrepid navigator of still very rough political waters, and infinite thanks for your intellectual guidance and inheritance.

O’Connor, il compromesso keynesiano e il ruolo dello stato

Il ricordo. Quando le funzioni dello Stato (politiche sociali, di repressione e di accumulazione) entrano in contrasto tra loro. Il dibattito degli anni Settanta tra marxisti

Enrico Pugliese

Edizione del18.11.2017

L’articolo di Giovanna Ricoveri (il manifesto) ha rievocato la figura di James’O Connor (Jim per i compagni) soffermandosi soprattutto sul suo impegno politico e culturale degli ultimi decenni in campo ambientalista: un impegno portato avanti senza mai rinunciare al suo approccio coerentemente marxista.

Lo sforzo teorico di O’ Connor – come ha sottolineato Ricoveri – è stato quello di illustrare la rilevanza di quella che lui definiva la “seconda contraddizione del capitalismo”, quella tra uomo e natura (dopo la prima tra capitale e lavoro).

Io vorrei soffermarmi invece su La crisi fiscale dello stato, il suo libro più famoso. L’edizione italiana pubblicata da Einaudi aveva una importante prefazione di Federico Caffè che chiariva un equivoco fondamentale che era sorto intorno al libro e che finiva per diffondere un messaggio antitetico a quello, per altro chiarissimo, che O’ Connor intendeva dare. Si tratta del costo enorme pagato dallo stato per il sostegno economico e politico al capitale monopolistico, che si esprimeva – allora come ora – nel complesso militare industriale.

Il libro – o forse semplicemente il suo titolo – fu spesso utilizzato a sostegno del credo neo-liberista, che in quegli anni cominciava e prendere vigore contrario all’intervento dello stato nell’economia e alla presunta incontrollata espansione della spesa pubblica per le politiche sociali (in particolare per i sussidi monetari agli indigenti: il welfare check.

Nella sua introduzione Federico Caffè sottolineava proprio questo punto, sostenendo che La crisi fiscale dello stato era divenuto «una specie di formula ad effetto volta a presentare l’immagine di uno stato che – vittima di apprendisti stregoni che l’hanno indotto a percorrere con leggerezza la strada dell’espansione della spesa pubblica – si trova ora di fronte a una situazione di dissesto».

E in effetti nel corso degli anni sessanta – quelli della great society Johnsoniana e della guerra alla povertà – la spesa sociale era cresciuta enormemente senza per altro riuscire a garantire un lavoro e una vita decente a quote molto estese della popolazione (soprattutto minoranze nere e ispaniche) anche se – val la pena ricordarlo – era riuscita a migliorarne le condizioni.

Sulla funzione di controllo sociale del sistema di welfare state americano O’ Connor non aveva dubbi. In questo concordava con i grandi studiosi del welfare dell’epoca: in particolare con Richard Cloward and Francis Fox Piven.

Ma per lui il problema centrale era un altro: quella della creazione continua di masse di poveri, che poi spettava allo stato mantenere.

Vale pertanto la pena di ribadire i punti rilevanti e originali del pensiero di O’ Connor al riguardo, inquadrandolo nell’ambito culturale della sinistra americana dell’epoca la quale trovava una voce colta e accademica nel Journal of Radical Political Economics.

Il suo punto di partenza è Il Capitale Monopolistico di Sweezy e Baran pubblicato una decina di anni prima: testo al quale si riferiscono (insieme a quello di Harry Bravermann Lavoro e Capitale monopolistico) molti di quegli studiosi, in particolare quelli che analizzavano vano i meccanismi di funzionamento e la struttura del mercato del lavoro, i giovani (allora) teorici della segmentazione e del dualismo.

Per questi ultimi il ‘compromesso keynesiano’ raggiunto negli anni trenta in America aveva garantito al settore forte e centrale della classe operaia (quello alle dipendenze delle imprese monopolistiche) sicurezza occupazionale e alti salari, scaricando sugli altri, quelli relegati nel ‘settore concorrenziale dell’economia’ il problema della precarietà e dei bassi salari. Lo stato – garante del compromesso – si accollava la responsabilità di provvedere al mantenimento della popolazione eccedente.

Nel libro successivo, Individualismo e crisi dell’accumulazione pubblicato da Laterza, egli allargava la sua ottica e dall’analisi economica a un approccio in cui gli aspetti sociologici e i contributi della teoria critica tedesca si aggiungono e rendono ancora più complesso il quadro.

Qui sottolinea come le diverse funzioni dello stato, quella di legittimazione (attraverso le politiche sociali), quella repressiva e quella di garantire il processo di accumulazione entrano in contrasto tra di loro. L’essenza delle scelte compiute in quegli anni – a partire dalla generalizzazione delle politiche keynesiane nelle loro varie edizioni e sotto le pressioni popolari e le esigenze di controllo sociale – è consistita nell’espansione dei consumi, nella crescente tendenza alla mercificazione dei beni e dei servizi (ed alla soddisfazione dei bisogni sotto forma di merci).

Per effetto di ciò il settore dei beni di consumo ha finito per espandersi a svantaggio del settore dei beni capitali.

La mancata espansione di quest’ultimo, anzi la sua effettiva penalizzazione, si traduce in una riduzione del livello di produttività del sistema. E in ultima analisi nella crisi dell’accumulazione. Ma all’origine di tutto c’è il processo di progressiva affermazione dei valori dell’individualismo penetrati anche all’interno della classe operaia americana, a spese delle strutture solidaristiche tradizionali.

Questi rilevanti nella visione di O’Connor trovavano una sede importante di dibattito nella rivista Kapitalistate (con la K in omaggio a Marx), che lo tenne impegnato soprattutto nella seconda metà degli anni settanta : una rivista importante e diffusa tra gli studiosi marxisti, soprattutto non ortodossi, all’epoca.

La sua visione dello stato non appartiene al marxismo tradizionale. Lo stato capitalista è di parte – ma non è il semplice ‘gabinetto di affari della borghesia’ – è soggetto attivo ma è anche terreno di scontro.

In quegli anni il dibattito sul tema è molto intenso tra i marxisti in Europa e in America. Ora del ruolo dello stato non se ne parla più tranne che per ribadire come per effetto della globalizzazione lo stato ha perduto peso e rilievo. E che forse l’importanza ad esso data dal marxismo dell’epoca era eccessivo.

Certo il passaggio da un epoca di politiche keynesiane a un epoca di politiche neo-liberiste ha mutato certamente il quadro. E le cose sono andate ancora peggio. Alla crisi fiscale e alla sua specificazione in termini di crisi dell’accumulazione è seguita una fase ancora peggiore: quella della riduzione estrema della spesa sociale da Reagan in poi che trova il suo coronamento in Trump.

James O’Connor – articolo per il manifesto

Giovanna Ricoveri (www.ecologiapolitica.org)

James O’Connor, nato nel 1930, professore emerito di sociologia ed economia alla University of Santa Cruz in California, è morto domenica scorsa 12 novembre 2017 nella sua casa di Santa Cruz. Accademico e studioso militante atipico e neo-marxista, da sempre impegnato nelle battaglie per la giustizia sociale nel mondo e per l’integrazione razziale negli Stati Uniti, ha scritto testi fondamentali per la comprensione del capitalismo, essenziali per capire e combattere contro la catastrofe chiamata capitalismo. Il più famoso dei suoi moltissimi libri tradotti in tutto il mondo resta La Crisi fiscale dello Stato del 1973, ed.it. Einaudi 1979, prefato da Federico Caffè, dove ha analizzato la natura contraddittoria dello stato, che pretende di essere indipendente dal capitale (dalle classi dominanti), mentre invece ne serve gli interessi, senza svolgere la funzione di mediatore di tutti gli interessi in campo al fine di raggiungere il bene comune generale.

La pubblicazione della rivista Capitalism Nature Socialism (CNS), da lui fondata nel 1988 e diretta fino al 2003, quando ha passato il testimone per ragioni di salute, ha segnato una svolta importante nel suo pensiero e anche nel suo modo di definirsi marxista e neo-marxista nelle mutate condizioni internazionali. “Nonostante l’ambientalismo costituisca uno dei più importanti movimenti sociali sia negli Stati Uniti sia negli altri paesi, e nonostante la crisi ecologica abbia ormai raggiunto il mondo intero, i marxisti e i socialisti hanno fatto finora pochi e deboli tentativi per dare una spiegazione teorica coerente di questi fatti”, affermava O’Connor nel 1988, nella Introduzione al primo numero della rivista statunitense, tradotta in Capitalismo Natura Socialismo n.1/1991. E’ di questo periodo la formulazione della “seconda” contraddizione, quella tra capitale e natura, seconda rispetto alla prima, quella tra capitale e lavoro – seconda perché emerge dopo la prima in senso temporale, senza tuttavia sostituirla (“La seconda contraddizione del capitalismo: cause e conseguenze”, Capitalismo Natura Socialismo n. 6/1992)

La rivista italiana, diretta allora da Valentino Parlato e Giovanna Ricoveri, e pubblicata nei primi anni da una società de il manifesto, nacque nel 1991 nel contesto di un network di riviste di ecologia politica comprendente anche la Spagna (con Ecologia Politica diretta da Juan Martinez Alier e la Francia con Ecologie et Politique diretta da Jean Paul Deléage), legate dalla stessa lettura della crisi proposta da O’Connor. La rivista italiana ebbe successo agli inizi, perché la critica di O’Connor ai vari marxismi allora esistenti –non a Marx – interpretava quella dei comunisti “dissidenti” italiani di allora e di una parte degli ambientalisti, su tre grandi temi: primo, che la crisi ecologica è causa di crisi economica e sociale, verità scomoda e per questo ancora oggi totalmente rimossa da politici ed economisti mainstream; secondo, che le due crisi sono due facce della stessa medaglia, come oggi afferma Papa Francesco; terzo, che i movimenti sociali – ambientalisti, femministi, urbani e dei lavoratori – sono determinanti al fine di superare la crisi della democrazia rappresentativa nella fase della globalizzazione finanziaria.

Le idee e i valori per cui Jim O’Connor ha vissuto e lottato non si sono certo inverati, ma sicuramente il suo impegno ha contribuito a tenerli vivi, e questo è quello che conta. Per me è stato un amico leale sin dal nostro incontro a New York, dove lui era già docente di labour economics al Barnard College della Columbia University, e io studentessa di economia alla Columbia. Non ci siamo mai persi di vista, e la nostra amicizia si è consolidata nella costruzione della rete di CNS, con incontri anche frequenti in Europa e in California, specie nella prima fase di questa iniziativa editoriale.

I was one of Jim’s grad students when he officially “retired” from UCSC. He was, literally, just coming out of the woods having just moved back into town as I started the program. He didn’t see much point in meeting me as an advisor until I’d completed the two theory and two methods seminars and passed the vile, two-day, stress test the department insisted was a measure of students’ worthiness to continue past the Master’s level. But those seminars were incapable of preparing me for Jim.

I had a degree in Biology, focusing on acid rain and freshwater for my senior research, and Jim knew I was there to work on whatever it was that environmental sociology was. At our first real meeting he handed me a list of 10-12 books on the idea and history of nature… not one by a sociologist. It was staggering but awesome. He also instructed me to sign up for the grad working seminar that Spring as a way of structuring my reading and socializing my learning process. It was the seminar that produced the first number of CNS. I sat in it, having found the first four seminars in the program very easy, with my jaw agape – I had never sat in a room filled with people of that intensity and intelligence and commitment to shared growth… I was sure I’d never measure up. I didn’t know that Jim – and some others – would make it so I had no choice but to become one of them.

He next gave me the top 10-12 books on theories of the state and, after a summer editing a volume on the political economy of agriculture for Bill Friedland, added me to the Santa Cruz editorial group. I thought he was nuts, what could I contribute, but figured I could do nothing but learn. Sadly, I know I was a too rough on some contributions – the idiocy of young insecure men covering their insecurity with bravado…

I’ll never know if he was just setting me up or if the idea just came to him but the following Winter quarter he “suggested” – it wasn’t a suggestion – that I read everything Murray Bookchin had ever written and prepare an ecological Marxist critique for my Masters. It turns out that Bookchin had written a lot of words since the early 50s. Moreover, Bookchin’s worked jumped all over the place historically, conceptually and topically. I wrote 90 plus pages of single-spaced commentary – drawing on my scientific background to critique Bookchin’s understanding of mutualism and my mother’s anthropological knowledge to reject his anthropological claims about the roots of domination. O’C liked it, but had a better idea… ouch. He wanted me to generate an account that synthetically straightened out the zig zag scholarship in Bookchin’s into a semi-linear historical trajectory… which took another year. He may have done this to give him time to introduce me to people who could redirect my intellectual and political frustrations with Bookchin into a respectful critique appropriate to his importance – something I didn’t understand or know how to do.

Jim was never easy, his standards were intense, his ideas were staggering and he could be really rough on people. Whether it was the fact that I was a male HS and college athlete from a particularly intense small college and used to being variously knocked around or the fact that, he said – early on, I don’t know where – that 1) the more and better work he thought you could do, the he beat of up your work and that 2) a critique of your research and writing is not a critique of your person and that it’s really important to know that sometimes you produce work that’s not as good as you’re capable of OR which stimulates in readers intense and challenging questions.

A real shift happened – and I learned something very important that day – in the next working seminar. Jim was working on an article for a high quality left journal and a pivotal element of it was conceptually wrong (I can’t remember if it was some element of natural science he missed or if the point he was making contradicted a logical extension of the second contradiction thesis) and I made a pointed and extended critical comment, including how the rest of the piece would have to be adjusted after he fixed the error. I distributed it to all the participants and only then realized that I’d just taken my advisor on… Jim’s reaction was so powerfully instructive, it stands out as one of the few key moments in my intellectual life. He reviewed it, agreed with it, said so in front of the rest of the seminar and changed his article. How many senior scholars do that?! He showed that he meant what he said, sometimes our work isn’t as good as it can be and a fair critique that offers a better way to go deserves respect. The next few months also showed me that he now thought of me, finally, as a future colleague rather than as someone to mentor.

I completed my dissertation, initially trying to prove the second contradiction with a case study… oops but finding it a remarkable tool for organizing historical data in a relational manner.

I’ll miss Jim even though we weren’t in much contact since my career took a turn and his health deteriorated. But, to my everlasting pride, Jim and Barbara invited me to Santa Cruz to help go through his papers 18 months ago and a better weekend I have rarely ever had. (And I have some critiques of Jim’s own use of his own thesis I’m going to keep on developing as a sign of my deep affection and unending respect.)

The sad news of Jim O’Connnor’s death led me back to the letters from him that I kept and treasured ever since we corresponded quite intensively over some three or four years in the early 1990s. Although a few were written in long-hand (one of these on well over 10 pages of foolscap), most were typewritten, with corrections and marginal comments added in pen. Some of what was in them was practical stuff related to him publishing in the Socialist Register, me in CNS, plans for him to speak in Toronto, me in Santa Cruz, etc. But so much more was intensely stimulating – even as reread now as it was then – that I can think of no way to offer a better testament to just how remarkably generous, insightful and prescient a socialist intellectual Jim O’Connor was than to share with you a few passages from a few of these letters.

Jan 27, 1992 (On how the “Discipline and Profit” book he was working on parallels some of the argument in my ‘Capitalism, Socialism and revolution’ essay in the 1989 Socialist Register): ‘The main point’ make in my chapter, or one of them, to put it in shorthand, is that Marx had labor, workplace, etc. right; but that he missed the anarchists and Polanyi’s “community” -based on “land “‘ the second fictitious commodity in Polanyi’s world. The anarchist have nothing interesting to say about labor; nor does Polanyi because he never followed Marx theorizing labor exploitation as (a) the domination of capital over labor, politically, culturally, ideologically, etc. and also (b) the source of inherent realization crises within capitalism, which drive the system. So I argue that the socialist project -now the ecological socialist project (because what is “land” besides space, soils, forests, etc. etc.) needs to sublate the traditonal socialist and anarchist projects – e.g. theories and practises of labor and land; planning and spontaneity; class and individual; the central and the local; etc. I.e. all the antinomies that everyone. talks about, like the weather but few are doing any real praxis about.”

June 20, 1992: ‘I was especially excited to read your democratic administration mss. In 1973 or 1979, after reading Colletti on Lenin, some Lenin himself, and after finishing Fiscal Crisis, which was inspired by the apparent displacement of worker struggles from the private to the public sector, I started Kapitalistate, with the aim of developing international positions on the whole problem of the state, bureaucracy, forms of administration, etc. Not being a political theorist by profession, I had lots of help from Offe and others who called themselves left Weberians at the time. As you know better than I, the 1960s was fundamentally a critique of bureaucracy (Terry Hopkins, Sociology, SUNY, Binghamton has written brilliantly on this) — from the left. Which created the political/ideological terrain for the critique from the right — neoliberalism. As a matter of fact, it was Murray Wienenbaum, ex-Boeing economist, who wrote a book on the “costs of regulation by Federal bureaucracies,” and who Reagan took aboard as his chief economist, who also led the move to fire yours truly from Washington University, St. Louis, in 1966. “You’re not an economist,” he said. True enough! Fact is that my mind was more on organizing the anti-war movement in St. Louis, 1964-1966, than it was on keeping up with economic theory, which, anyway, I was abandoning for sociology, history, and. ..a more refined Marxism. Small world department. Anyway, in K-State #7, published in 1978, I turned out the enclosed. Please consider it an acknowledgment for your more refined, much better written, and of course more up to date mss., which I read with great interest. Barbara, my partner in crime, also. She who coined the term “popular bureaucracy.” I should have known that you would be working on the problem of democratic administration, complete with conferences on same, since from a Marxist point of view, the only political goal (as contrasted with political means to social, economic, etc., ends) possible in liberal democracies is to put democratic content into the shell of procedural democracy. Someday, when we meet and have time, I would like to tell you all my stories about the struggle for democratic administration (which is better than “democratic state”), including defeats within the state agency I work for — the UC system — at the hands of “leftist” colleagues who believe that democracy is too “unruly” and “messy” (actual quotes). I learned through these and many other battles that with power comes responsibility, and with responsibility comes hard work, and few have the time or energy or guts or all three to do this work except in times of extreme emergency, e.g., our last earthquake. Most people seem to want power without responsibility, which is one definition of fascism. And responsibility with power is what grown-ups demand of kids. So while democratic administration is the only plausible political goal there is, one that fits classical Marxism as well as the radical democracy of post-modernism/post-Marxism (which I think is afairly important point), as well as conforming to common sense. I’ve learned that it’s the hardest thing in the world to pull off. Yet, the most important thing to work on, and toward.’

December 24, 1994: I just read your SR essay and like very much the way you pose and deal with the problem of globalization and the state… The context, as I see it, for your essay is something like this: While GDP growth rate fell by 50 percent after the mid-1970s, setting off a process of “accumulation through crisis,” pioneered by Japan, spreading to the US and UK, and now haunting EC, especially Germany, Asian growth has been spectacular. I should say “Asian accumulation,” since it’s the rapid rate of capital accumulation in Asia that is the main source of extreme competition faced by US, Canada, etc., capitals. Or, at least, has been until quite recently. I like your idea that states help to author capital globalization. Way I see it is that states become more capitalist states and less states in capitalist societies, if you know what I mean. Clearly, until recently, the whole show was, as you say, linked to the “reproduction of American capital.” This is especially true of Japan, which had to adjust to every change in US foreign policy. But now this is changed: it appears that the US got everything it wanted with GATT/WTO, but my guess is that problems of interpretation, enforcement, etc., will multiply right through the turn of the millenium…. As for the crisis tendencies in the new global model, it’s not only (as you mention) that export-led economies generate, finally, problems of insufficient effective demand. My work shows that the main G7 countries, in the course of “accumulation through crisis” since the mid-1970s, have shifted resources from Department II to Department I (especially high tech equipment and services) for a decade and a half. The composition of capital is higher in Department I than Department II, hence you get a shift of income from wages to profits and a shift in capacity from consumer goods to capital goods. The Old Mole called this a tendency toward a “disproportionality crisis,” which is a replay of the 1920s (cf Sid Coontz’s underground classic, Unproductive Labor and Effective Demand). This is a perfect set-up for the main G7 countries to mount big export drives to Asia and Latin America in capital goods, e.g., large-scale passenger aircraft, telecommunications, contract construction, etc.). This seems to be what’s happening. Asia and LA buy US, German, and Japanese capital goods and services (or entice FDI), which increases their capacity to produce cheap wage goods for export to G7, especially the US. Presto, the production of relative surplus value, as the cost of the average consumption basket in the States becomes cheaper (housing excepted). This turns out to be the model Marx develops in Capital. Politically, then, everything depends on close alliances, e.g., between the US government and the Chinese CP, which were once the worst of enemies and are now the best of friends, since without the CP, China would soon fall into chaos and the magic China market would evaporate. So no longer is it the US that every other state has to adjust to, in one way or another, but Asian authoritarian capitalism, which is being imported piece by piece into the States (and Canada?) You can see why I like your essay so much, not just because it is so thoughtful and lucid, but because it presents aline of thought about the politics and the state which compliments the economic analysis I’ve been working on!’

In the years 1969 to 1974, I have greatly benefitted from my intense intellectual exchange with Jim O’Connor. During the months of his visit in the early 70ies at the Max Planck Institute I was working with at the time, I remember him lying flat on the floor of my office in order to minimize his chronic back pain while delivering his arguments with ready-to-print clarity. His original ideas on the political economy of the capitalist state have influenced my own work on capitalism and democracy for many years to come more than those of any other author (with the possible exception of Karl Polanyi whom Jim also held in high esteem). His analysis of both fiscal and accumulation crises turned out to be prophetic, as was his Marx-inspired analysis of the “second contradiction” of capital vs. nature which anticipated much of today’s environmental, climate and degrowth concerns and movements.

In addition to being a highly original theoretical thinker, O’Connor was a great teacher. When visiting him at the UC Santa Cruz in 1974, I was struck by his sociology-of- knowledge approach to social theorizing. Whenever we teach a theory, we must ask, he argued, who (in terms of class politics) is typically inclined and interested in having that particular theory in question and its underlying assumptions widely accepted as true and valid. We shared an interest in the key question of what makes people think and reason the way they do, and which structures and agents shape their thought and ideological affiliations.

While his Fiscal Crisis book continues being appreciated as a classic among political economists and sociologists, his later work on accumulation crisis and the “Economic Theory of Government Policy” remain relatively unknown in Europe. There remains much to be (re)discovered in the work of the great theorist and activist Jim O’Connor.

My deepest condolences to the family. Jim was a friend of my father’s for many years. He was also my professor at UC Santa Cruz and his teaching was profound.

Jim O’Connor was not only my most important mentor in college, he was a great friend. There were times when we would be shooting pool and drinking beer in a local saloon and Jim would spit out one of his brilliant insights into how the world worked, and I would have to grab a napkin and write it down, often asking him to please restate the gem he had uttered. Other than my parents, Jim taught me more important lessons than any other human. In the mid-1970s, while getting a BA at Sonoma State University, I was lucky enough to read Jim’s awesome book Fiscal Crisis of the State, which explains how monopoly capitalism tends to bankrupt government–and that books is still relevant today after more than 40 years. That book and his other writings caused me to apply for the brand new Sociology PhD program at UC Santa Cruz where Jim had been hired. Jim served on my dissertation committee and gave me super-helpful criticism on my writing. He would send me back chapters with red ink all over them (this was before computers), prefacing his critiques by saying, “Open a beer, sit down, and remember I am your friend in making the criticisms you are about to read.” And his suggestions for improving the manuscript were always right on target.

I am SO SO glad that Jim played an important role in my life. If more people had Jim’s brilliance and intellectual courage, we would replace this destructive economic system with one that puts life values ahead of money values.

Rest in peace Jim–you had a very positive impact on so many of us. We love yiou.

Jim the Great was a magnificent mentor, prodigious and incisive intellectual, impassioned comrade, overly-confident poker player, heck of a party host, spinner-extraordinaire-of-yarns, unrepentant arguer, and dear friend.

From literally the first day I arrived at grad school at UCSC, 40 years ago, Jim took me under his very wide and luminous wing.

One of his many generous gifts was to help arrange a wonderful research and teaching gig for me in Madrid in the early 1980’s. When I arrived, I was welcomed by a bevy of politicos, journalists, scholars, and activists, including the Spanish Civil War revolutionary heroine, “La Passionara,” Dolores Ibárruri. All due to my connection to “Jaime O’Connor, El Gigante Intelectual Mundial” (“the giant, global intellectual.”) And when he came to visit us in Spain, what an appropriately “red” carpet they rolled out for him.

Others of you have detailed Jim’s important intellectual contributions. I would add that one of his very finest accomplishments was to help shape his two smart, compassionate, and beautiful sons, of whom he was justifiably proud.

I offer many thanks to Jim’s devoted companera, Barbara, who was an amazing partner to Jim not only in love, but in labor, social justice, humor, and intellect. Barbara, you are magnificent.

Companero Jim O’Connor, Presente!

– Karen Hossfeld, Sociology Faculty, San Francisco State University

I never met James O’Connor in person. But when I was a graduate student at Columbia in the early 1970s, I was among the first, I believe, to buy his Fiscal Crisis of the State book and, of course, read it. My heavily annottated copy migrated several times with me and my family across the Atlantic, and stayed with me until today. A few years ago when the financial crisis of 2008 convinced me that social democracy had run its course, and the study of labor and industry was no longer enough, I pulled it from my shelf to read it again. The book that I subsequently wrote, Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, owes enormously to O’Connor’s sophisticated reading of the fiscal sociology tradition that goes back to the early Schumpeter and, not to be forgotten, Rudolf Goldscheid. For example, the analytical sequence I develop in the book from the tax state to the debt state to the consolidation state builds in a major way on O’Connor. To me his book was and is a classic, which may explain why I never expected to meet its author in person. Now I know that I could and should have tried, but it is too late. Still, I can epxress my gratitude to an original thinker capable of inspiring theoretical work over a distance of almost half a century.

I remember well my first encounter with Jim O’Connor. It was early February 1975, I spent a couple weeks in the Bay Area and called up people who might have some advice for my doctoral project. I wanted to know about the different modes of accumulation, from merchant capital, small commodity production, and yeoman farming to slave plantations and later the extractive industries in the West, and how the tensions and contradictions between them had shaped the emerging nation state created in the late 18th century. Jim had invited me for 10 am, so I followed his directions to the old white cottage up on Congo Street and was greeted to the smell of fresh roasted coffee, frying bacon, and Camel cigarettes. Seeing my baffled face, he explained that it was neither tobacco nor pork that was killing people, but capitalism.

I had barely sat down when he told me that, instead of doing more reading I should go find leftist historians and talk to them to get at their empirical knowledge, because no one had dealt with the questions I was asking. He assured me these were important questions and we explored why and how they mattered and were politically relevant, to this day. He put me in touch with such historians as Dale Tomich, and also with people working on Marxist state theory at the time and those who he thought understood the unique American form of capitalism. After my questions were attended to, he shared what obsessed him at the time, the “never-yet-proletariat” as a subject, and the conversation touched on all that seemed relevant to this question: capitalism in transition, the role of the state, world markets.

I was fascinated, I wanted more.

When I got myself got back to the Bay Area in 1980/81, this time with a grant, and started researching urban movements at UC Berkeley, we were able to pick up the thread; I joined the Kapitalistate collective and his circle of friends and comrades. Our encounters became more frequent and more intense in 1984, as I returned on a two-year Habilitation (the second PhD in the German system) stipend, and especially a year later as I landed a Visiting Professorship at UCSC – we had become colleagues.

It was such a gift to be close to his perceptive mind, his fearless critique of the powers that be, and his incessant search for “the subject”, which led him to pay attention to the struggles that expressed whatever conjunctural contradiction of capitalism, from the public employees’ struggles to ecological movements. His house was always open for those keen to understand the unfolding ways of class struggle. He was a voracious reader, the tables and chairs were usually piled high with newspaper clippings and new books, and he thrived on dissecting with us the latest contradictions of capitalist economics, culture and politics and, increasingly, of (second) nature.

For some years after, Santa Cruz became my second home, and when there we spent countless hours discussing, at his home, or walking through town, or along Fall Creek in Henry Cowell State Park. On these walks, he would often interrupt the political or theoretical conversation to point out local sites of history, vestiges of earlier struggles that few Santa Cruz residents are aware of. I remember fondly many walks up to the limekilns with him and with Barbara as our local expert and guide.

After he and Barbara founded CNS in 1988, I was lucky to be involved in this project even while living in New York or in Germany: over acquiring authors or editing manuscripts I managed to stay close to their power house of hard-hitting analysis and eco-socialist theory-building. While pushing this ambitious project, with an editorial board spread not just across North America, Jim always remained full of good advice for my own projects, always curious about what was happening in my part of the world, and incredibly big-hearted while critical and direct. As the testimonials show, he was that to so many of us. Thank you, Jim, and thank you, Barbara, for allowing me to be a collateral beneficiary of your love story.

Appeared in Monthly Review, January1, 2018

With the death of James O’Connor in November 2017, at age eighty-seven, the world lost one of the foremost Marxian political economists (and contributors to Monthly Review) and a key figure in the ecosocialist tradition. Writing twenty years ago in the Review of Radical Political Economics, MR editor John Bellamy Foster called O’Connor “the leading representative of ecological Marxism.”

O’Connor will likely be best remembered for two achievements: his landmark book The Fiscal Crisis of the State (1973), which brought altogether new elements to bear on Marxist theorization of the state; and his role in founding the journal Capitalism Nature Socialism in the 1990s, developing in the process a distinctive approach to ecological Marxism known as the “second contradiction theory.” His most enduring contribution to the ecological discussion was undoubtedly his incorporation of Marx’s concept of “conditions of production” into an ecological critique of the system, in what has been described as a synthesis of the ideas of Marx and Karl Polanyi.

In addition to his contributions as a major Marxist theorist, O’Connor, as his long-time partner Barbara Laurence rightly reminds us (“James O’Connor Testimonials,” Center for Political Ecology, http://centerforpoliticalecology.org), was a political activist, especially in his early years. This included “his days in Cuba helping to stabilize the revolutionary government; his leaving relatively safe New York for the dangers awaiting his bus caravan to the South during the Freedom Rides; and his part in organizing the Faculty Against the War during the horrible days of Viet Nam.” In this and many other respects, he was a model for us all.

Joan Martínez Alier

Before I met Jim O’Connor in person, sometime in early 1989 in the beautiful campus of Santa Cruz of the University of California, I had read already his anticipatory book The Fiscal Crisis of the State of 1973 and the introduction that he wrote to the first issue of Capitalism, Nature, Socialism in 1988 on the “second contradiction of capitalism”. He edited this journal with Barbara Laurence for some years, until bad health made him to stop. The journal continues to this day, and from the beginning it was a sister journal to Ecología Política (published in Barcelona by Editorial Icaria and its director Anna Monjo), Ecologie Politique (issued in France by Jean-Paul Deléage), and Capitalismo Natura Socialismo (the Italian journal edited by Giovanna Ricoveri). These alliances have endured until today.

For some years we had a close relationship. In the first issues of Ecologia Política we translated many articles from CNS, although I had a pro-peasant, pro-Narodnik bias that amused him a little. We never had a political disagreement, and whatever I would include in Ecologia Política he would agree with, attributing any surprising material to my anarchist inclinations to be expected from somebody from Barcelona (meaning the Barcelona of 1936). He came to Barcelona for the launching of Ecología Política in 1991. We organized debates on the “second contradiction of capitalism” in Ecologia Política, translated from CNS but also with original articles. I believed and still believe that the “second contradiction” was a brilliant concept that helped to make sense of the myriad movements for environmental justice around the world.

The word “eco-socialism” (misappropriated by a post-communist party in Catalonia) was introduced in Barcelona in this launching meeting of Ecologia Política in 1991 organized also by the environmental sociologist and professor at the UAB, Louis Lemkow. We were all eco-socialists, and still are. But in my case I was socialist in the sense of the First International, with anarchists, Russian pro-peasant populists, and Marxists trying to live together – which unfortunately proved impossible in 1871. Later, the Marxists split into two main currents, the “German” Social Democracy and after 1917 the Leninists, both equally oblivious (in my view) of ecological issues.”Eco-socialism” had to go back to 1871, adding ecologism and feminism to socialism, and looking at the whole world and not only to Europe. We broadly coincided with Jim O’Connor in this view. The main article in the first issue of Ecologia Politica was not by Jim O’Connor or by myself but by Victor Toledo, the Mexican ecologist and pro-peasant eco-socialist. I also introduced in Ecologia Política and CNS the knowledge I was gaining at the time of the “environmentalism of the poor” in India and Latin America.

In his book of 1973, The Fiscal Crisis of the State, which anticipated the crisis of Keynesian social-democratic capitalism of 1975 and the rise of neoliberalism with Reagan and Thatcher, James O’Connor had argued that the capitalist state had to fulfill two fundamental functions, namely accumulation and legitimization. To promote profitable private capital accumulation, the state was required to increase taxes in order to finance the welfare state, increase social security, lower the reproduction costs of labour, and thereby increase the rate of profit of capital, at the same time maintaining social harmony through social expenses, for instance on unemployment and health benefits. All this became contradictory. It implied increasing taxes, and there would be a capitalist rebellion against taxation, as indeed it started in California. The state would enter into a fiscal crisis. The budget deficits became associated with the idea that government had become overloaded, that full employment was no longer an objective of macroeconomic policy, that trade unions were too powerful. The neoliberals were to preach a roll back of the state.

In 1988, Jim O’Connor came out with a resounding new thesis in the introduction to the journal Capitalism, Nature Socialism. The issue was not only that investment in the search of profits increased productive capacity while exploitation of labour decreased the buying power of the masses. This was the first contradiction of capitalism. There was a second contradiction. The capitalist industrial economy undermined its own conditions of production (he should have said, in my view, the conditions of existence or the conditions of livelihood, and not only the conditions of production).

There was exhaustion of natural resources, there was introduction of dangerous technology like nuclear power, there were new forms of pollution, and capitalism had not the means to correct such damages. A new type of social movements were arising, and the main actors were not the working class but an assortment of social groups, often led by women, often composed of ethnic minorities. The fact that the “environmental justice” movement had arisen in the US in 1982 inside the Civil Rights movement, reinforced Jim O’Connor’s thesis, and his journal published several articles on this movement that fought against “environmental racism”.

To me Jim O’Connor (and before him, in 1986, Enrique Leff’s “Ecologia y Capital” which I persuaded Jim to have translated into English) were main sources of inspiration for the work I have done and still do (being ten years younger than Jim) on the global movement for environmental justice and the EJAtlas. He knew that I was grateful to him.

https://onedrive.live.com/view.aspx?resid=546FB70B5BA0EFB9!14587&ithint=file%2cdocx&app=Word&wdo=2&authkey=!AGCLoX8Y_MGOrWU

I attach a small artricle (for a German monthly journal „Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik“) on the changes in the relations between capital and the state which Birgit Mahnkopf and I have dedicated to Jim

All the best

Elmar

Entitle Blog In memory of James O’Connor (1930-2017) – I part

https://entitleblog.org/2017/12/29/in-memory-of-james-oconnor-1930-2017-i-part/

and

II part

https://entitleblog.org/2018/01/05/in-memory-of-james-oconnor-1930-2017-ii-part/

“It is with great sadness that I receive this news from Joan. I was thinking of Jim very often in the last months and wanted him to know I had planted a sequoia tree in my small forest as a symbol of our friendship. The only time we met was in his house in Santa Cruz one weekend in the 90s. We shared long conversations and a lovely concert. Next day Barbara took me to the sequoia forest. Jim was not only the pillar of eco-Marxism. He was a very open-minded intellectual. Not only did he publish my Ecologia y Capital as Green Production to open his series on Ecology and Democracy in Guilford. He took the initiative to translate and publish other of my incipient writtings, not particularly Marxist in the core of their arguments, in CNS, a rare generous gesture in any “orthodox” disciplinary field and in the Anglo academia. To seal this friendship and alliance, his Natural Causes was published by Siglo XXI Editores in Mexico and his fundamental thinking has been widely disseminated in the Spanish academia.

My condolences to Barbara and to all of you that shared with Jim our common purpose in life.”

I am very sad that I won’t be able to attend this event. Jim was a massive support to me in the early days of my work. He enabled me to attend conferences in New York, Costa Rica and Santa Cruz. I know he was equally supportive to other young scholars. We all owe him a huge debt – I certainly do.

Congrats and best wishes to CNS on its 30th birthday.

Mary

Very many thanks for the invitation. I won’t be able to get there, but am very pleased that this tribute is happening. Jim’s work has been a great influence on my own thinking, and early on he was personally very encouraging.

all good wishes,

Ted

Jim was never too far from my thoughts.

I acknowledged his presence and influence in what I’ve written,

principally Territories of Difference (2008), that has a section devoted

to his thought (the Second Contradiction), and in a book on design to come

out next month, where I again acknowledge his work and CNS as one of my main

sources of learning about ecology.

interface

optical